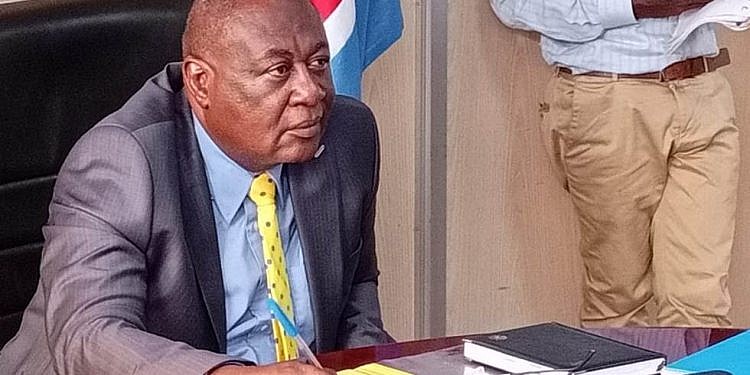

By Dr Sam Mayanja

The Judiciary power is derived from the people and exercises its mandate under the constitution as per Article 126 in the name of the people and conformity with the law and with the values, norms and aspirations of the people of Uganda.

The independence of the judiciary is not achieved in an instant act, but rather over some time by a continuous struggle which takes place within the framework of an ongoing and dynamic process.

At Independence in 1962, Uganda inherited a judicial system which was an integral branch of the executive rather than an institution for the administration of justice. The colonial administration was mainly interested in the maintenance of law and order.

It had no respect for the independence of the judiciary or the fundamental rights of the ruled.

The judiciary was that part of the structure which enforced law and order. The colonial judiciary was, therefore, an instrument of control of the executive power, lacked credibility and therefore enjoyed little respect.

The 1995 constitution marked a departure from this colonial narrative when under Article 126 (1) a definitive description of the role of an independent judiciary responsive not only to the law but also to the values, norms and aspirations of the people of Uganda is given.

This sanctity of the people is guaranteed by the vesting in an elected President, all Executive Authority under Article 99 (1) of the Constitution, and Article 99 (2) vesting in his mandate to execute and maintain the constitution.

Accordingly, when the values, norms and aspirations of the people of Uganda are ignored by the Judiciary itself, the constitution has mandated the President to intervene in his capacity as the last bastion of constitutional enforcement under Article 99 (2).

Accordingly, when the Judiciary orders properties like Mosques or Churches to be put on sale by public auction or private treaty in disregard of the citizen’s values, norms and aspirations towards places of worship, orders bibanja holders to be evicted ignoring their right to security of occupancy, orders bibanja holders to forfeit their holding without compensation, alienates public land to traditional rulers, or sacrifices substantive justice at the altar of legal technicalities, then a situation arises for His Excellency to exercise Presidential mandate under Article 99 (1) (2) to safeguard people’s aspirations under Article 126 (1) and 126 (2) (e) and intervene guiding the Judiciary back to the constitutional path.

The independence of the judiciary does not mean just the creation of an autonomous institution free from the control and influence of the executive and the legislature.

Rather it must be seen within a structure where judges are appointed according to their merits, academic credentials, seniority, and other conditions established by the laws of Uganda bolstered by a system where persons selected for judicial office are individuals of integrity and ability.

This method of judicial selection safeguards against judicial appointments for improper motives and is cardinal to the independence of the Judiciary in Uganda.

It is further bolstered by adequate remuneration, conditions of service, pensions and the age of retirement being adequately secured by law. The Judges, have guaranteed tenure until a mandatory retirement age.

The provision in Article 99 (1) (2) and (3) ensures that the independence of the judiciary is not used for one department of government to be in a position to dominate the others.

It should rather be seen within the constitution which provides for the composition and powers of the executive, the legislature, and for the judiciary. A constitution is one living organ, no one article destroys the other, rather they all support each other.

It must be recognized that in the Third World Countries where Uganda is one, there are times when there is a complete constitutional breakdown or revolution, which occurs because of constitutional inadequacy or of a successful coup d’etat generally followed by imposition of martial law or army rule.

This constitutional breakdown creates an environment in which constitutional and conventional restraints become inoperative. The legislative and judicial branches become subordinated to the executive which may itself become subordinated to the military.

In the landmark case of ex-part Matovu, the Court took judicial recognition of a successful revolution.

Sometimes in the life of the nation, circumstances which are not legal but political arise where the solution can only be political.

An example is when an extraordinary situation arises and the government must declare a state of emergency and judicial independence gives way to executive and security management of a situation which has arisen. It is a situation beyond the judiciary-courts do not decide political questions.

It must always be borne in mind that judges are, after all, human and although they are professionally trained to be fair, and fearless in discharging their functions, they are as wearable as anyone else to human frailties.

It therefore becomes clear that achieving judicial independence is not only legal but a social, cultural and political problem as well, rendering Article 99 (2) politically and judicially imperative.

Dr. Sam Mayanja is the

Minister of State for Lands

smayanja@kaa.co.ug

www.kaa.co.ug